David Ruggles

(1810-1849)

Abolitionist and American Hero

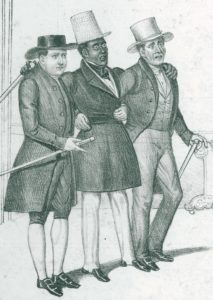

David Ruggles was an African-American abolitionist, writer, publisher and hydropathic practitioner who was a courageous voice of black freedom. He assisted hundreds escaping slavery, and mentored future abolitionist luminaries Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and William Cooper Nell.

Early Years

David Ruggles was born in Norwich, Connecticut in 1810, the eldest of seven children, to free black parents. His father, David Sr., was a blacksmith. His mother, Nancy, was a noted caterer and a founding member of the local Methodist church. Ruggles was educated at religious charity schools in Norwich.

Anti-Slavery and Racial Equity Activism in New York

By 1827, Ruggles was in New York working as a mariner. In 1828 he opened a grocery shop. By the early 1830s, Ruggles became involved in the growing anti-slavery movement in New York, advocating for “practical abolitionism,” arguing that abolitionists should not just philosophize about the day slavery would end, but strive to help all victims of human bondage. He also advocated the use of civil disobedience and self-defense.

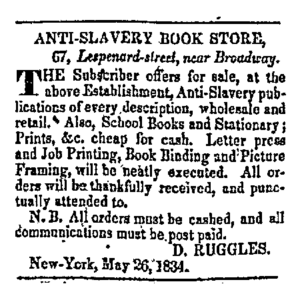

Ad for Ruggles Book Store

Ruggle’s grocery shop at One Cortlandt Street was also a circulating library and reading room for African Americans who were denied access to New York’s public libraries. His was the nation’s first black-owned bookstore, and there Ruggles sold anti-slavery publications until it was destroyed by a mob. In 1833, The Emancipator, an abolitionist weekly, appointed him as an agent to canvas for subscribers throughout the mid-Atlantic states. By 1834, now on Lispenard Street, Ruggles was also writing regularly, publishing dozens of articles and pamphlets for newspapers throughout the Northeast. Between 1838 and 1841 he wrote, printed and published the first journal edited by an African-American, The Mirror of Liberty.

David Ruggles was a visible “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, and helped at least 600 enslaved people to freedom, including Frederick Douglass. Ruggles was also a founder of the New York Committee of Vigilance which fought against the practice of kidnapping free Blacks in New York, as well as fugitive African Americans, and illegally selling them into slavery in the South. Ruggles would openly confront “kidnapper” slave catchers, and the Vigilance Committee offered their victims legal assistance. Ruggles himself experienced at least one such attempted kidnapping.

His brazen and courageous anti-slavery activities made Ruggles one of the most hated abolitionists in New York. In addition to his attempted kidnapping and several efforts to lynch him, his store was burned down, and he was physically assaulted multiple times. Even some other Black abolitionists criticized his tactics as too extreme and subject to scandal. All this took its toll on Ruggles’ health, leaving him weak, ill and nearly blind.

Recuperation at the NAEI and Reinvention as Water Cure Doctor in Florence, MA

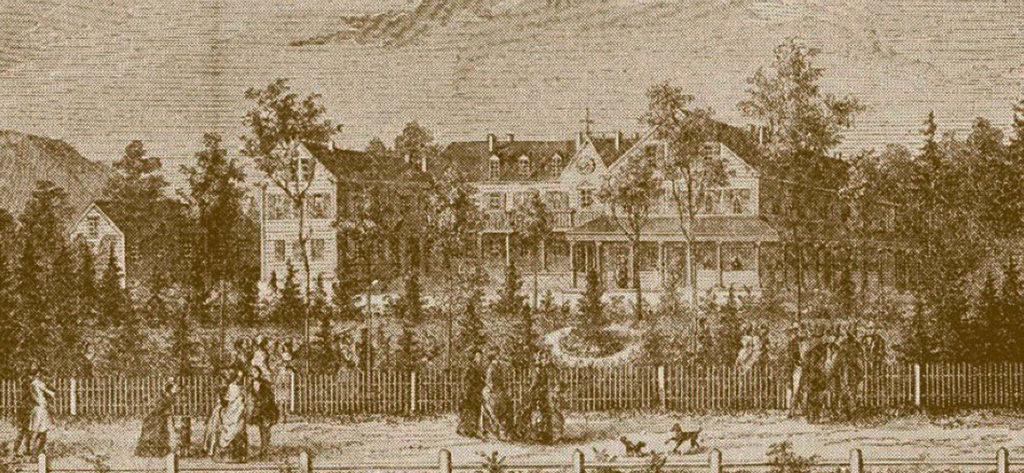

Ruggles house: Site of his first water cure establishment

In 1842, in failing health, Ruggles moved to what is now Florence, Massachusetts; his name being put before the membership committee of the Northampton Association of Education and Industry, a “utopian” community established by abolitionists. As he settled in Florence, Ruggles found much needed companionship and rest. He soon organized a rally of Black citizens to support imprisoned Massachusetts abolitionists Charles Torrey and Jonathan Walker.

Treating himself with the techniques of “Watercure,” then in vogue, David Ruggles recovered some of his sight and much of his health. In 1847 he erected the first building in the nation dedicated exclusively to hydropathy. Perhaps his most famous patient was William Lloyd Garrison, but he also treated luminaries Lucy Stone, Mary Brown -John Brown’s wife-, and Catherine Beecher, as well as Sojourner Truth.

Water Cure Establishment

Ruggles continually suffered from poor health, the result of injuries incurred by his anti-slavery activism in New York. Tragically, at the young age of 39, his ailments flared up again, and on the 16th of December, 1849, David Ruggles died in Florence, Massachusetts.

Portrait of Frederick Douglass, attributed to Elisha Hammond. Hammond was a member of the Northampton Association. Letters from Dolly Stetson to her husband James, published in Letters from an American Utopia, mention Douglass’s portrait being painted during his visit in 1845.

What I Saw at the Northampton Association, by Frederick Douglass, 1894

In 1894, the renowned statesman and abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote his recollections of meeting David Ruggles, published in “What I Saw at the Northampton Association” in Charles Sheffield’s History of Florence, 1894.

“Here, at least, neither my color nor my condition was counted against me. I found here my old friend, David Ruggles, not only black, but blind, and measurably helpless, but a man of sterling sense and worth. He had been caught up in New York City, rescued from destitution, brought here and kindly cared for. I speak of David Ruggles as my old friend. He was such to me only as he had been to others in the same plight. Before he was old and blind he had been a coworker with the venerable Quaker, Isaac T. Hopper, and had assisted me as well as many other fugitive slaves, on the way from slavery to freedom. It was good to see that this man who had zealously assisted others was now receiving assistance from the benevolent men and women of this Community, and if a grateful heart in a recipient of benevolence is any compensation for such benevolence, the friends of David Ruggles were well compensated. His whole theme to me was gratitude to these noble people. For his blindness he was hydropathically treated in the Community. He himself became well versed in the water cure system, and was subsequently at the head of a water cure establishment at Florence. He acquired such sensitiveness of touch that he could, by feeling the patient, easily locate the disease, and was, therefore, very successful in treating his patients.”